Is the Covid-19 pandemic causing us all to become “Fashion Victims”, I wondered after reading “Are mink farms the source of Covid in Europe ?” at the end of December.

A follow-up article by Yann Faure and Yves Sciama for the French online ecology review Reporterre has continued their investigation, this time questioning sources in China. The search for the cause of the globetrotting, species-hopping virus is honing in on Chinese fur farms and the frivolous and barbaric fur industry as a whole as the potential culprit.

« Are mink farms in China at the origin of Covid-19? The clues are piling up…

What if the pandemic originated in intensive fur farms in China? The ‘missing link’ between the bat and the human may well be the mink – the raccoon dog is also suspected.

This would explain the stubborn desire of China – the world’s largest fur producer – to block scientific information. The birth of Covid-19 on a farm of Chinese fur animals – and especially mink – seems increasingly plausible, as this survey shows. At the end of December 2020, Reporterre revealed that the strains responsible for the two waves of epidemics that ravaged Europe had appeared in the immediate vicinity of large mink farms. Reporterre continued the investigation on the Chinese side. Just today, Friday, January 8th, 2021, Science published an article highlighting the need to study the link between Covid and minks.

Are they going? Not going? At the time of this writing, no one knows whether the delegation of scientists selected by the World Health Organization (WHO) will indeed travel to China to investigate the origin of the pandemic. The ten international experts have still not received the necessary permits to enter the territory. Negotiations are underway, but the opacity is such that no one knows the stakes.

It is astounding that a year after what is shaping up to be the largest pandemic of the past century, no progress has been made in understanding how Sars-CoV-2 may have been transmitted to humans from bats, its natural host. An uncertainty that is not due to the limits of science, but indeed to the attitude of the Chinese authorities, who for a year now, have been opposing, tooth and nail, any independent attempt – even if it came from within the country – to answer this question. We wonder what China absolutely wants to hide.

It is difficult not to note, in particular, that no investigation has been carried out to confirm or deny a hypothesis that is as obvious as it is rarely mentioned: that of an origin of the pandemic in a farm breeding animals for fur. China is indeed both the world’s largest market and producer of fur, and the colossal Chinese branch of this industry weighs in excess of twenty billion dollars annually, with over fifty million pelt-producing animals. However, if traditional farm animals (cattle, pigs, poultry, etc.) do not appear to be infected with the coronavirus, the reverse is true for fur animals: the three main species – mink, fox, and raccoon dog – are highly sensitive to the virus.

All specialists know that there is nothing exceptional about human epidemics originating on breeding farms. The latter are known microbial culture broths: the last influenza pandemic of 2009, for example, originated on American pig farms – hence its name swine flu. Moreover, the ‘corona-virologist’ Christian Drosten, discoverer of Sars-CoV-1 in 2003, and scientific advisor to the German government, said in April 2020 in an interview with the Guardian: ‘If someone gave me a few hundred thousand dollars and a pass to China to find the source of the virus, I would look in the places where raccoon dogs are raised.’

The hypothesis put forward by Christian Drosten that the raccoon dog could be the missing link between the bat (the original host of this coronavirus, according to scientific consensus) and humans, makes sense. Raccoon dogs (Nyctereutes procyonoides) – often mistaken for the raccoons they look like – are small carnivores in the canine family.

A team led by Conrad Freuling of the German Federal Institute for Animal Health Research, located in Riems, experimentally demonstrated in August 2020 that these animals not only catch the human coronavirus, but also transmit it.

‘We found that the virus remains confined to the nasal cavity in this species, and does not reach the lungs’, indicates the researcher, interviewed by Reporterre. Consequences? ‘They barely get sick when infected, and remain asymptomatic while being contagious. In addition, they a priori excrete enough virus to infect a human.’ This property brings them closer to mink, as we have seen in farms in northern Europe. The researcher notes that being highly transmissible and not very pathological is the profile of a very adapted virus, which is entirely compatible with the hypothesis according to which these species are the “missing link” between the bat and the human.

But if Christian Drosten suspects the raccoon dog, it is above all due to the SARS pandemic of 2003. Because if it has been repeated many times that the animal which spread this disease (of which Sars-CoV-1 was the agent) was a viverrid – the masked civet (Paguma larvata) … raccoon dogs were also contaminated and just as likely to have played the role of transmitter to humans!

In scientific studies dating from 2003-2004, focusing in particular on the markets of Shenzhen, in Guandong, it seems almost impossible to determine which of the two species first infected the other or whether a third infected both at the same time. As an April 2007 article in Virus Research indicates, the masked civet is considered the most likely last intermediate host before humans. One of the main reasons cited was the identification of nearby restaurants where infected civets were found and where three customers and a waitress fell ill. It’s slight evidence. All the more so as civets, which were bred for several decades for their fur before becoming a famous consumer meat, numbered in those years only 40,000 head in the whole country. In other words, a very small potential reservoir. The number of farmed raccoon dogs is estimated at between five and ten million.

In 2003, China seems to have maneuvered to criminalize the civet in order to distract attention from its fur industry. In the winter of 2003-2004, a huge survey funded by the Chinese Ministry of Science and Technology and the US National Institute of Health, involving the sequencing of a sample of 1,107 civets from 23 farms selected in twelve provinces, concluded that if, in the Xinyuan market (Guandong), the 91 civets present were indeed carriers of the virus, there was no detectable infection in the farms of origin of the civets sold. Indication that the contamination could have taken place rather at the market or during transport. However, in the same Xinyuan market, all of the fifteen raccoon dogs present were infected.

Although several articles have pointed out that these civets could have simply been contaminated by raccoon dogs, no studies have been launched to find out more about raccoon dogs. Several researchers were surprised, including Paul and Martin Chan, who complained that these animals ‘do not elicit any interest.’ Shi Zhengli, undoubtedly the main Chinese ‘corona-virologist’ who heads a department at the Wuhan Institute of Virology, regretted, in 2007 in the article of Virus Research already mentioned, that it is ‘still not clear whether it was the raccoon dogs that infected the civets or vice versa.’ And concluded: ‘Unlike civets, very little research has been done to sample wild or farm raccoon dogs.’

We encounter this same astonishment from Conrad Freuling, who admits that he also tested raccoon dogs in Germany because no one had ever done so in China, where almost all the farms in the world are located – there are only a few in Finland and Poland. Finally, it should be noted that in these markets, red foxes and mustelids were also infected. Oddly enough, the Sino-US study did not sample any farms in Shandong, Liaoning, Jilin or Heilongjiang, the four main mink breeding provinces. Not having investigated Shandong is particularly surprising, since it is the unrivaled capital of fur production and the province is geographically closer to Guandong than Hebei – which has been thoroughly surveyed.

So in 2003 it was as if China had maneuvered to criminalize the civet, a species of marginal economic importance, in order to distract from its lucrative fur industry, so as to protect it. However, this same strategy seems to have been repeated and taken to a higher level in 2020 – in an obviously different context and with colossal stakes. This time around, China has clearly decided to totally control scientific discourse on the pandemic, just like it controls civic discourse.

After an initial phase of confusion in January and February 2020, during which we saw both journalists and high-ranking scientists publish relatively freely, repression descended on the former (with convictions and even disappearances), and censorship on the latter. The information is obviously filtered and shaped according to the objectives of those in power in China.

More precisely, a recent investigation by the Associated Press (AP) reveals that the government has engaged in a vigorous takeover of scientific publications after the publication of an article by two researchers in February – an article now found on the internet, suggesting that the virus had escaped from a laboratory in Wuhan. Consequences, as of February 24th: a new procedure for publication approval by the Chinese Center for Disease Control (CDC), then the release of a confidential ministerial note, dated March 3, which the AP obtained and uploaded. The content of it is striking, calling for ‘coordination of the publication of scientific research on Covid-19 across the country in the manner of a game of chess’, under the control of a ‘research group Council of State scientists’ and after having notified the ‘propaganda’ team of the said Council. The memo bans any publication that is not validated by this group – and concludes that violators ‘will be held accountable.’

It is therefore on this note that we must approach recent Chinese scientific publications: despite the excellence of a large number of researchers, the information is obviously filtered and shaped according to the objectives of the authorities. The same goes for the press: for months, there was no mention of foxes, minks and raccoon dogs in the inventory of animals present at the Wuhan market before it closed on December 31, 2019.

Yet, according to the latest WHO report, foxes were present in the city’s ‘wet market’. And according to a risk assessment released in March by the Center for Infectious Diseases and the Canadian Public Health Agency, mink was also on the list of animals for sale. Finally, in photographs taken in early December 2019 inside the market and broadcast in January 2020 by CNN, there were also raccoon dogs in this famous market. No matter what the authorities said, the trio of farmed carnivores was therefore complete in the Wuhan market.

Note that although these species have been the subject of a media blackout, the Chinese Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs has not forgotten their existence. When it was necessary, under the pressure of world public opinion, to ban the trade in wild animals because of the risks of viral emergence and spread, he reclassified them as ‘domestic species’ in order to exempt their breeding from any possible hindrance.

Let us also evoke the planetary success of the fable of the pangolin. No less than four Chinese articles have come out to incriminate this scaled animal. The theory of the pangolin, now abandoned, since the virus found in this animal is even more distant from Sars-CoV-2 than that of the bat, was proposed even though the sequencing of the viral gene that it was supposed to carry was far from complete. Just before, Chinese authorities had already managed to fuel the press with the hypothesis that the snake was probably the intermediate host. In the aftermath, there was even an attempt to feed the theory of the turtle to public opinion. All false leads! One cannot help but think that directing all eyes to three species with scales cannot be entirely a coincidence; so many similar suspects effectively distract the public from fur producers.

The most likely intermediate host based on recent research? Mink. Yet after the Southern University of Agriculture bluntly communicated, without any supporting data, the focus on the pangolin, a study contradicting the previous one went largely unnoticed. January 24, 2020, as can be seen on the Global Times website, which has been keeping the epidemic’s diary since its inception, the most likely intermediate host according to General Database Comparison (GISAID) research using artificial intelligence software is … mink. Mink even has the potential to be the original host.

However, this study, which targets mink, was initiated with the support of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, the Wuhan Virological Laboratory and the Chinese CDC. The work of Quian Guo’s team offers every guarantee of seriousness, and its results have not been disputed. But, except in Singapore and Australia, his work wasn’t given a hearing. That omission ensured that the pangolin, reinforcing prejudices and exacerbating passions, saturated all available information space.

Another edifying example of delaying publications by the Chinese scientific community is the study by Shandong Medical University, which appeared April 1, 2020 in the Medical Journal of Virology. The researchers tested, from the structure of their receptor protein – the one on which the virus binds – 85 species of mammals: human, cat, dog, pig, horse, civet, pangolin, macaque, fox, raccoon dog, African elephant, meerkat, bull, polecat, kangaroo, opossum, turtle, lynx, etc. But they ‘forgot’ the mink, however particularly present in the region of origin of the researchers, namely in Shandong, where there are no less than fifteen million!

Scientists concluded, without laughing, that it would be good to carefully monitor a cetacean, ‘the Yangtze finless porpoise, because it is found in lakes near Wuhan and could be infected with the Sars-CoV-2 or related coronavirus’. It is also amusing to note that their study finds that in small carnivores, cats included, there is a distinctly lower affinity for Sars-CoV-2 than for cows or sheep, although we now know that the reverse is true.

There are three thousand Chinese mink farms, some of which hold in excess of one hundred thousand animals. Chinese minks, and especially those from Shandong, are worthy of attention. As we know, the last few months have scientifically demonstrated that mink can both contract the virus from humans and infect them in return, frequently generating mutations in the process.

But beyond this news, there is a long history of mink diseases, which shows that this solitary species – like all farmed carnivores, while herbivores are social – placed in the conditions of appalling promiscuity of fur farms , contracts multiple diseases that make them a health threat. However, those three thousand Chinese mink farms, some of which exceed 100,000 heads may well be the source of the current pandemic. It is therefore incomprehensible that no viral research has been published concerning these animals.

Some examples of the problem? In 2011, a new virus excreted by farmed mink was genetically detected on a farm in Hebei. It appears to be a virulent reassortment of usually benign human and porcine virus strains. 100% of the mink were affected, 5% died. The occurrence of necrotizing encephalopathy in two children was considered likely to be attributed to this recombination, and the study published by Emerging infectious diseases concluded that preparations should be made for the emergence of more virulent variants.

In 2014, mink on a farm in Shandong suffered from an epidemic of porcine pseudo-rabies that killed 87% of the animals and spread throughout the province. The scientists who had tried to assess the scale of the epidemic in fourteen localities said in their publication that the virus has a very high infection rate in the region and that ‘this poses a challenge for the fur industry.’

In 2015, a team (including Chinese virologist Shi Zhengli) isolated and identified bat viruses closely related to human, porcine and mink viruses which suggests interspecies transmissions between bats and humans or animals.

In October 2016, a team from the Quingdao Veterinary College discovered that minks in Shandong were infected with highly pathogenic H5N1 avian influenza.

In 2019, another team from the same Quindao veterinary college spotted the emergence of a deadly co-infection of the distemper virus and the H1N1 swine flu in mink farms in Shandong, resulting in a new H1N1 strain in the infected lungs of these mustelids.

Farmed mink are also possible intermediate hosts for influenza A varieties which may lead to the development of human pandemic strains by direct or indirect transmission. They sometimes harbor the hepatitis E virus in an epidemic manner, but it is not yet known whether they can transmit it to humans. They are monitored for BSE (bovine spongiform encephalitis) due to their diet partially consisting of animal meal, etc.

To limit the potential damage, minks are vaccinated against the viruses that most commonly affect them, such as Aleutian disease parvovirus, which is highly contagious for their species as well as the distemper virus, transmissible among canines. Mammals with fragile lungs, they spontaneously catch pneumonia, which they spread easily because they have the particularity of sneezing, just like ferrets, who are also mustelids. Both mink and ferrets carry specific coronaviruses, that of ferrets being called ‘systemic’ because it affects all organs, while that of minks is called mink CoV (MCoV).

Bats, attracted to breeding sheds, defecate … on cages Finally, to take the measure of the microbial cauldron represented by these farms, note that Chinese mink are particularly concentrated in the Shandong region. This historic land of fur farms is home to thousands of farms, sometimes with multiple activities. As we have seen, fifteen million mink are confined there (in addition to three million raccoon dogs and six million foxes). Most are in a limited area which stretches south from the coastal commune of Weifang.

The animals, crowded together in sometimes frightening hygienic conditions, are partly fed on fresh fish from the Yellow Sea, poultry or pig offal, animal meal and carrion from their relatives who are cut up after being skinned. High protein fresh food is important to improve the quality of their fur. Their existence, entirely captive, is rather brief: mink, for example, reproduce in March, give birth in April and litters are killed between mid-November and mid-December. Only the ‘stallions’ and the females intended to reproduce the next generation are spared. However, these breeders represent around 12% of the number of mink on each farm, which may be sufficient for any existing pathogens to persist.

Let us add that Shandong, a territory of low-range mountains and forests, known among other things for its caves, is home to many species of bats, some of which, such as Rhinolophus ferrumequinum, Myotis Fimbriatus or Eptesicus Serotinus, are carriers of coronavirus. Bats are attracted to breeding sheds, which provide them with potential shelter. They urinate and defecate frequently on anything they fly over…cages containing animals for example. In fact, we therefore have in Shandong (even if this is also the case in other regions of China) all the ingredients for formidable viral encounters, recombinations of all kinds and dazzling disease emergence.

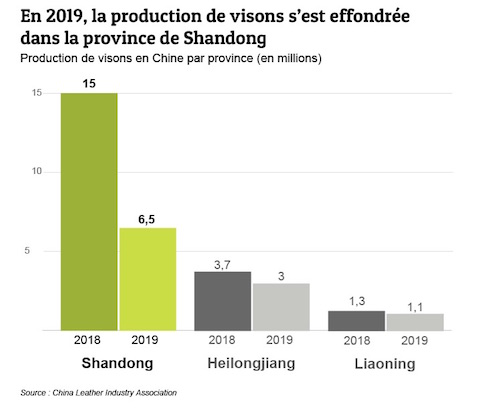

An obscure numerical calculation attracts attention: in 2019, the province harvested just 6.5 million mink pelts, down from almost 15 million the previous year. Almost nine million mink vanished from one year to the next! A drop of 55%, unique to this province alone, which seems to be explained only by a disaster or a brutal scourge. Which? Could it have been sanitary? This is particularly curious since the production of fox skins (5.7 million) and raccoon dogs (three million) from the same territory have remained perfectly stable. Asked several times by Reporterre to explain this discrepancy, the China Leather Industry Association laconically cited in an email ‘a stagnant market and an overproduction of mink skins’ which would have led ‘most companies to leave the industry’. An explanation that seems insufficient given the magnitude of the earthquake.

Therefore, all the major mink pelt producing countries would have been contaminated… except China? In any case, it is surprising that officially no Chinese intensive mink farm had been contaminated while Eastern, Western, Northern and Southern Europe, the United States and Canada were affected. It would be an astonishing anomaly: all the major producing countries would have been hit, but the main one would be an exception, despite the many trade and professional ties uniting it with its foreign partners, notably the U.S., Northern Europe and Italy.

Ultimately, mustelids, canids and viverrids – mammals suspected of playing the intermediary role – are the same today as they were for the Sars-CoV-1 epidemic in 2003-2004. Except that masked civets are now a thousand times less numerous in the country than foxes, raccoon dogs and mink raised for their fur. It therefore seems inconceivable for the establishment of the truth and for preventing a future pandemic that the WHO does not order a close investigation of the fur farms, in Shandong and elsewhere.

It is clear from reading the preparatory WHO report, despite the perceptible diplomatic precautions vis-à-vis China, that the intention is there. It is, for example, indicated that the committee of experts plans in particular to ‘map the supply chains of all animals sold on the market’, wild and domestic, with a view to identifying ‘interesting geographical areas for carrying out animal and human serologies’. Therefore – exactly what should have been done for the past year: searches for viruses in and around fur farms.

Unfortunately, the WHO, after making multiple concessions to the Chinese regime, abandoned the ambition to directly practice fieldwork by signing a protocol delegating this part of the investigation to local researchers. The mission is not even expected to leave Wuhan, and one of its members recently told the journal Science et Avenir that we should not ‘expect the team to come back with conclusive results.’ Even thus disarmed, this delegation seems to continue to pose a problem in Beijing.

However, the wall erected by the Chinese state seems to be starting to crumble. On January 8th, an article signed by eminent Chinese researchers, namely Zhengli Shi and Peng Zou, for the first time recognized in the columns of the journal Science that mink could be the host ‘of the virus which generated the SARS-CoV-2’. The researchers even suggest conducting ‘retrospective investigations of samples dating from before the pandemic in mink or other susceptible animals.’

Suspicious minds will wonder why this suggestion comes so late, since mink’s susceptibility to Covid has been known for six months, and whether such samples still exist. Others may find it better late than never. »

That ‘s my translation. Here’s the link to the original article in French:

8 janvier 2021 / Yann Faure et Yves Sciama (Reporterre)

UPDATE from Chinese news source: Apparently, as of January 11th, according to an article by Teddy Ng and Simone McCarthy in the South China Morning Post, the WHO coronavirus investigation team is finally scheduled to arrive next Thursday, January 14th.

Their report: « Brief announcement from Beijing follows confusion and delay after visa ‘misunderstanding’… The international experts will work with Chinese scientists to determine virus origin, health commission says.

The World Health Organization team investigating the origins of Covid-19 will land in China on Thursday, Beijing announced on Monday, after days of delay and confusion.

The National Health Commission said in a brief statement that the WHO team would work with Chinese scientists during the trip, without giving further details.

WHO chief Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said last week he was ‘very disappointed‘ that China had not yet finalised permissions for the team. Two members had already begun their journeys and others were not able to travel at the last minute.

But Chinese foreign ministry spokesperson Hua Chunying said ‘there might be some misunderstanding’, and that Chinese authorities were in close cooperation with WHO to handle the pandemic.

On Saturday, Zeng Yixin, deputy director of the National Health Commission, said China ‘enthusiastically supports the expert group’ and their research, but added the timing had yet to be worked out. The WHO on Friday said they hoped travel dates for the mission would be fixed this week.

Last week’s delay placed another question mark over the mission, which has been in the works for months and faced criticism over a lack of transparency as well as concerns that it was too late – more than a year after the virus was first identified in China’s Wuhan.

The probe, meant to uncover the animal origins of the virus which causes Covid-19, was called for as part of a resolution passed at a meeting of the WHO’s governing body in May.

But politics around the origins of the virus have complicated the mission. The US under the Trump administration has sought to blame China for the outbreak, while Beijing has launched a campaign questioning whether the virus emerged in China or was merely first identified there. China has characterised the WHO mission to China as the ‘China part’ of a global effort to identify the origins of the virus, and the WHO has said the mission could lead scientists out of China.

In July, two WHO experts travelled to China and worked with health authorities there to compose the terms of reference for the mission, including research to be conducted by Chinese scientists and an international team of experts. The UN body at that time said the mission may begin in a ‘matter of weeks’.

The international team and Chinese counterparts held their first meeting, online, at the end of October, after a selection process for the international experts, which included a submission of candidates to Beijing. They have held four meetings so far, China’s National Health Commission said on Saturday.

The field mission is meant to begin in Wuhan, and will include delving into hospital records to identify cases that may have existed earlier than the first ones identified in China in December, 2019. Research will also include looking again at the seafood market that was linked to the first known cluster of patients. Its role, either as the site where the virus first spilled into humans or as a location where the virus spread quickly among people, remains unknown.

Chinese scientists are expected to have already begun the work, with the international expert team reviewing data and findings. The mission is expected to last six weeks, including a travel quarantine period. »

The link to the original article in the South China Morning Post is here:

WHO coronavirus investigation team to arrive in China on Thursday | South China Morning Post

So, after the travel quarantine period, « research will also include looking again at the role of the seafood market »? Does the field mission plan include investigating the 85 species of mammals: human, cat, dog, pig, horse, civet, pangolin, macaque, fox, raccoon dog, African elephant, meerkat, bull, polecat, kangaroo, opossum, turtle, lynx, etc as well as the Yangtze finless porpoise, mentioned by Reporterre? Will they, once again, « forget » the mink; the most lucrative victim of the luxury fur trade? Animals used to be the only « fashion victims ». It now seems plausible that we are all victims of the luxury fur trade, humans as well as the pelt-bearing animals we exploit. Humans are the only animal that kills for vanity.

Now our vanity is killing us!

Part 1, the origins of Covid-19 in Europe, is here:

We Are All Dying for Luxury (Literally) ! ? Part 1 – the origins of Covid-19 in Europe

Fascinating! Thanks for those two detailed articles. I await with baited

LikeLiked by 1 person

breath the WHO report.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes! I hope the WHO is allowed to go where they need to!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Absolutely

LikeLike

Pingback: We Are All Dying for Luxury (Literally) ! ? Part 2 – the origins of Covid-19 in China — Barbara Crane Navarro | Ned Hamson's Second Line View of the News

Pingback: We Are All Dying for Luxury (Literally) ! ? Part 2 – the origins of Covid-19 in China — Barbara Crane Navarro – Tiny Life

Pingback: We Are All Dying for Luxury (Literally) ! ? Part 1 – the origins of Covid-19 in Europe | Barbara Crane Navarro

Reblogged this on Barbara Crane Navarro.

LikeLike